Offsite manufacturing, workerless building sites – what opportunities and challenges will technological advancements pose to the construction sector in the medium to long-term? How will firms integrate them into their everyday working practices and how will the insurance industry continue to respond?

This article is the second in a four-part series. To register to receive future updates from our construction team, please visit the dedicated sign-up page.

The first article in this series considered the here and now; technologies in the process of being adopted by UK and international construction organisations and the risks they pose.

This second installment is more of a future-gazing piece, looking at opportunities technology could present to the construction industry in the medium and long term and the challenges these opportunities might pose. How will construction firms integrate these changes into their everyday working practices and what changes will the insurance industry have to make to continue to respond to them?

Gazing into the crystal ball two, even three decades ahead, there are three themes that I have chosen to focus on – offsite manufacturing, the design process and workerless building sites. Some of the technologies I will cover are available now on a small scale but are set to develop significantly in the future. I also discuss other technologies that are not yet available at all, but are sufficiently advanced that we can discuss their eventual adoption with some confidence.

Offsite manufacturing

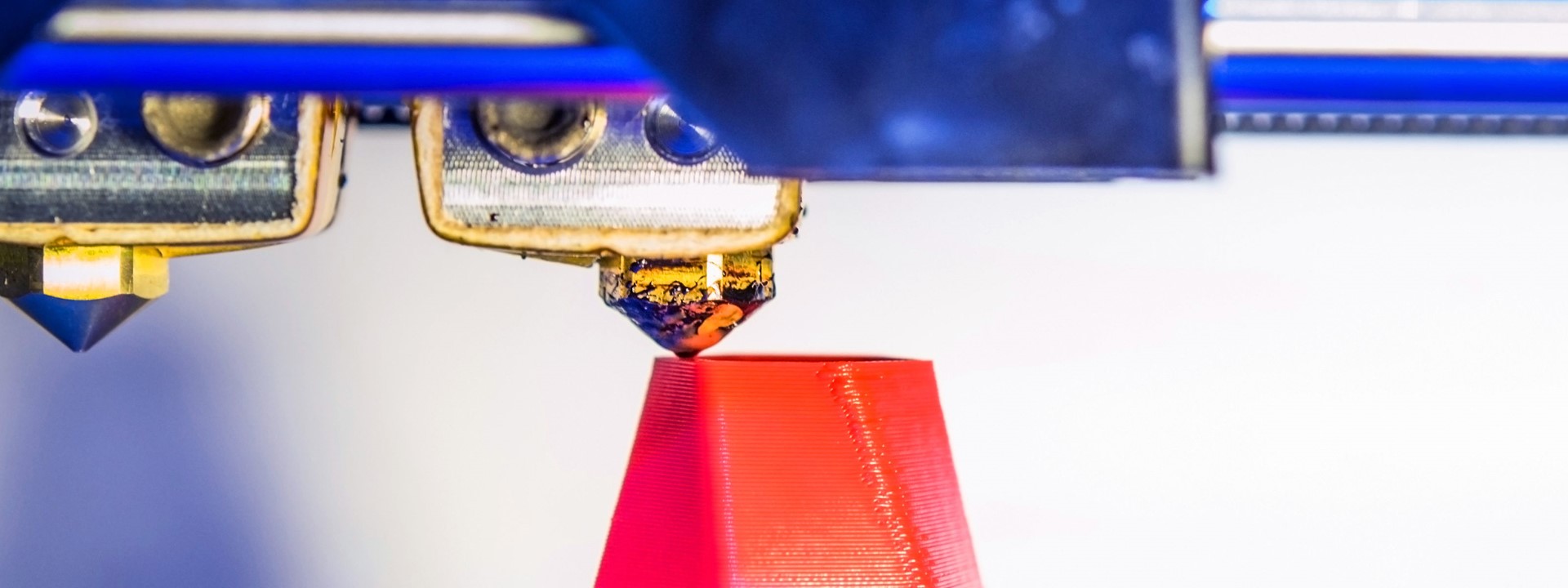

Beginning with the pragmatic; offsite manufacturing does not sound revolutionary but taken into the future, it has the potential to transform construction sites. A trend that began with pre-fabricated buildings after World War II has in recent years become more accepted as a standard method of delivery with offsite manufacture and transport techniques at the forefront of progress. 3D printing technology, though in its infancy, has the potential to open up even more exciting opportunities within this area.

There are many strands to offsite manufacturing, one example being the delivery of complete prefabricated buildings in sections. German firm Huf Haus is considered a pioneer in this field, having constructed a significant number of private homes with these methods already.

What other pre-fabrication techniques are currently available?

One which excites the inner child in all of us is LegoTM-like Logix insulated concrete forms. The principle is a set of insulating blocks which click together like bricks, ready to be filled with concrete, creating instant walls. This technique is considered by many to be a precursor to the real revolution: self-printing houses.

An experiment in China has already seen several single-storey concrete dwellings printed and assembled in a day. While the giant printers required to do this are not yet tested or industry-ready, the concept of feeding your finalised building design into a computer’s memory and watching on while the walls are printed in front of you is a highly appealing one.

It is claimed in some quarters that this concept should not be considered science fiction, as this is a technology almost ready for use. More cynical individuals within the industry claim it will take time to build a case for trust in the technology and therefore – investment. Questions have also been raised about the on-site technology required to deliver it, forcing firms to evolve their processes, software, systems and people skills.

In theory, a business case will be made once the cost of adoption roughly equates to the labour saving the technology delivers. For all these reasons, many believe we are still at least 10 years away from this concept coming to fruition. When it beds in however, I believe the effects will be felt everywhere.

The design process

Touched upon in the first article in this series - technological change in the design process is being spearheaded by Building Information Modelling (BIM).

As a reminder - BIM is not a system or software but a process that requires a project team to work together using a single digital storage centre for all design and build documents. It brings different groups together in a single collaborative working space, giving them access to current documents, from architect to sub-contractor.

Level 2 BIM envisages everyone on a site using the same 3D virtual model of a building. While BIM Is here now, it is some way off reaching its true potential. In theory, once the humans who operate BIM systems have perfected their feeds of information into this virtual building, it should be possible to hand a design to an automation architect, a job role that is currently sought after in fintech and service industry software development but will feature in project development over time.

The automation architect of the future will collate the right set of automated processes to construct a particular building, assemble and programme their delivery units, and hand on the package to the construction overseers (replacements for builders). At present, of course, an automation architect is a human, but it is not unthinkable that artificial intelligence could be added to the BIM suite of tools, allowing the programme to organise its own construction.

For those managing risk this could present a challenge, but what will make this safe is the determination of architects, construction companies and insurers to ensure that the systems are rigorously tested before being used commercially. Our job as insurers will be to model the risks in advance and feed back to our clients on the dangers we observe. The client will then be free to focus on making the software and robots work. These developments are a long way off, but this could be where BIM will ultimately take us.

Workerless building sites

I would like to finish with what can be a persistent scare story for our industry: the remarkable idea of workerless building sites. While sending a shiver down every paid employee’s spine, there is much to be said for partial automation of the construction process. Aspects of our work are dangerous, dirty, cramped or at height and can involve incredibly hazardous materials. Indubitably - humans are much safer when not exposed to these dangers.

The pioneering work in the field of workerless sites has been done at Chernobyl in the Ukraine, where the dangers presented by the highly radioactive and partially destroyed Reactor No.4 have led to the development of a completely remotely managed demolition programme.

In a scenario that could have been concocted by a science fiction writer, the New Safe Confinement building constructed over Chernobyl’s Reactor No.4, will be completed in November 2017. When finished, automated demolition vehicles and cranes will be sealed inside the building, in the area where it is unsafe for humans to work. These self-managing devices have a time-horizon of around 40 years to demolish the original sarcophagus which was built around Reactor No.4, as well as the nuclear core inside it. Untouched and unreachable by humans, the robots will work for decades to bring waste out of the NSC building, to a safe area where it can be partially decontaminated and taken to a safe storage facility built nearby.

While this might be an extreme (and remarkable) example, US firm Construction Robotics has already developed SAM (Semi-Automated Bricklayer), a bricklaying robot that can lay 3,000 bricks per day – six times the rate of a human bricklayer. This robot is already in use on sites in the US, and is set to launch in the UK in the next year. Looking at warehousing and production lines, it is easy to see how in a decade from now, large parts of repetitive construction site work might be managed by robots.

However, even SAM has to have a human overseer, and it is difficult to imagine that the many small changes and risks that have to be constantly evaluated and steered around by human builders can all be managed safely by even a new generation of robots. As a risk specialist, I applaud the automation of many hazardous and monotonous construction tasks, but I remain to be convinced that a human-free building site can be made viable and safe.

But what of overall insurance risks? Everywhere within the examples I have highlighted in this article, the themes are the same, technology will replace repetitive and hazardous tasks within construction, while factory-style techniques will bring automation to sites everywhere. While the technology has to be tested, if the promise of these new developments comes to fruition, in 50 years’ time, building sites will be safer, less crowded, and therefore potentially easier to insure. But the mistakes, when they are made, may be bigger, harder to foresee and spotted much later in the process, unless humans remain diligent.

While manual labour may take a step back on site, our human skills are not to be dispensed with yet. We will be needed on site for much longer than you might have been led to believe. Technology brings new opportunity, and equally it also needs to be heavily monitored to deliver structures that are sound and safe for all users.

In the next in this series of articles, I will make a more detailed assessment of the overall impact of technological change on insurance policies, risk management and approaches to claims.

Do not hesitate to contact me if you would like to arrange a discussion on this topic. You can sign up for the other articles in this series by completing our online form.

Would you like to know more?

To register for future updates from our construction risk specialists, please click here.

For further information regarding our construction practice, please click here.

To view a selection of QBE’s most recent insights, please click here.

Din kontakt

Din kontakt

Andy Kane

Portfolio Manager Construction