Three things to take away

What is the outlook for Sweden and Denmark’s trade in goods – and how is the geopolitical and economic landscape impacting growth prospects.

What are the key risk areas for firms involved in global commerce in 2024.

What can firms engaged with international trade do to mitigate risk and promote growth by tapping into due diligence checks, joint ventures and other financial products.

Denmark and Sweden are strong supporters of international trade and open economies so reducing regulatory barriers and enabling growth are key focus areas in both countries. While supply chain challenges in both countries have eased, ensuring secure supply in critical sectors will continue to be a focus for both governments.

Over the coming decade the governments in Denmark and Sweden have significant investment ambitions which will require inward investment, particularly in the energy sector – therefore both countries are likely to continue to encourage foreign investment going forward.

What is the outlook for Sweden and Denmark’s trade in goods – and how is the geopolitical and economic landscape impacting growth prospects.

What are the key risk areas for firms involved in global commerce in 2024.

What can firms engaged with international trade do to mitigate risk and promote growth by tapping into due diligence checks, joint ventures and other financial products.

Denmark and Sweden are strong supporters of international trade and open economies so reducing regulatory barriers and enabling growth are key focus areas in both countries. While supply chain challenges in both countries have eased, ensuring secure supply in critical sectors will continue to be a focus for both governments.

Over the coming decade the governments in Denmark and Sweden have significant investment ambitions which will require inward investment, particularly in the energy sector – therefore both countries are likely to continue to encourage foreign investment going forward.

Introduction

Denmark and Sweden are strong supporters of international trade and open economies. The outlook on trade for both countries is positive and there is no credible scenario in which a government would seek to restrict international trade. The governments in each country have not made any unexpected moves since taking office in the last quarter of 2022 and both are focused on providing stability into the 2023/24 winter. Reducing regulatory barriers and enabling growth is a key focus in both countries.

Both countries have healthy export industries, and both rely on imports for critical goods including in the energy and construction sectors. While supply chain challenges in both countries have eased, ensuring secure supply in critical sectors will continue to be a focus for both governments.

Disruption to import logistics would have strong flow-on effects and while the likelihood remains low, a disruption in the Baltic Sea related to the Russia-Ukraine war would have a sizable impact on both countries – particularly Sweden, which relies on an open Baltic for a large proportion of imports.

Over the coming decade the governments in both countries have significant investment ambitions which will require inward investment, particularly in the energy sector – therefore both countries are likely to continue to encourage foreign investment over that period.

Denmark and Sweden are strong supporters of international trade and open economies. The outlook on trade for both countries is positive and there is no credible scenario in which a government would seek to restrict international trade. The governments in each country have not made any unexpected moves since taking office in the last quarter of 2022 and both are focused on providing stability into the 2023/24 winter. Reducing regulatory barriers and enabling growth is a key focus in both countries.

Both countries have healthy export industries, and both rely on imports for critical goods including in the energy and construction sectors. While supply chain challenges in both countries have eased, ensuring secure supply in critical sectors will continue to be a focus for both governments.

Disruption to import logistics would have strong flow-on effects and while the likelihood remains low, a disruption in the Baltic Sea related to the Russia-Ukraine war would have a sizable impact on both countries – particularly Sweden, which relies on an open Baltic for a large proportion of imports.

Over the coming decade the governments in both countries have significant investment ambitions which will require inward investment, particularly in the energy sector – therefore both countries are likely to continue to encourage foreign investment over that period.

Denmark and Sweden’s trade in goods

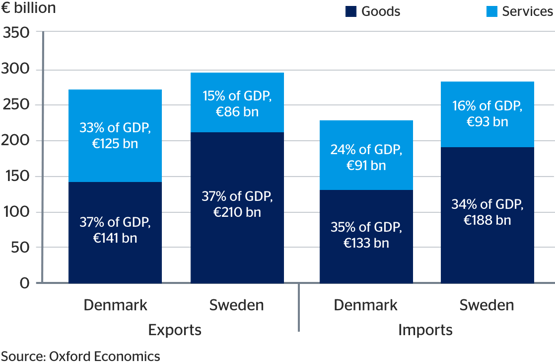

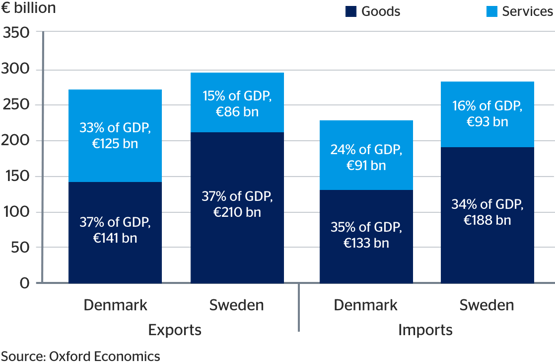

In 2022, Denmark exported and imported €141 billion and €133 billion worth of goods respectively (Fig 1). For Sweden, goods exports and imports were worth €210 billion and €188 billion respectively. For both countries, exports and imports of goods is larger than exports and imports of services. Goods exports made up 37% of each country’s GDP, whilst goods imports made up 35% of Denmark’s GDP and 34% of Sweden’s GDP.

In Denmark, machinery and equipment and pharmaceuticals are the biggest players, exporting €7 billion (20%) and €6 billion (17%) respectively. Food products, beverages and tobacco are the third, with exports of €6 billion (14%). In Sweden, vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers were the largest exporting sector, exporting €19 billion (13%). This is followed by basic metals €18 billion (12%) and paper products and printing €16 billion (11%).

For both Denmark and Sweden, the largest manufacturing industries that exported goods are also amongst the largest importers of goods.

Fig 1: Denmark and Sweden’s export and imports of goods and services in 2022

In 2022, Denmark exported and imported €141 billion and €133 billion worth of goods respectively (Fig 1). For Sweden, goods exports and imports were worth €210 billion and €188 billion respectively. For both countries, exports and imports of goods is larger than exports and imports of services. Goods exports made up 37% of each country’s GDP, whilst goods imports made up 35% of Denmark’s GDP and 34% of Sweden’s GDP.

In Denmark, machinery and equipment and pharmaceuticals are the biggest players, exporting €7 billion (20%) and €6 billion (17%) respectively. Food products, beverages and tobacco are the third, with exports of €6 billion (14%). In Sweden, vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers were the largest exporting sector, exporting €19 billion (13%). This is followed by basic metals €18 billion (12%) and paper products and printing €16 billion (11%).

For both Denmark and Sweden, the largest manufacturing industries that exported goods are also amongst the largest importers of goods.

Fig 1: Denmark and Sweden’s export and imports of goods and services in 2022

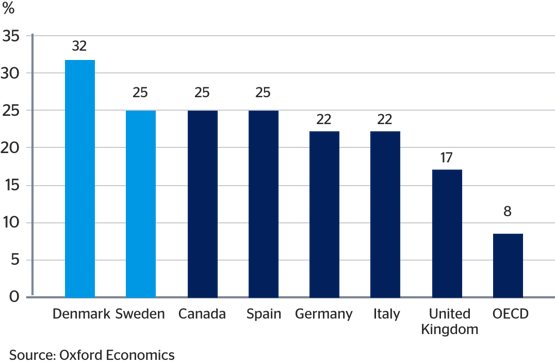

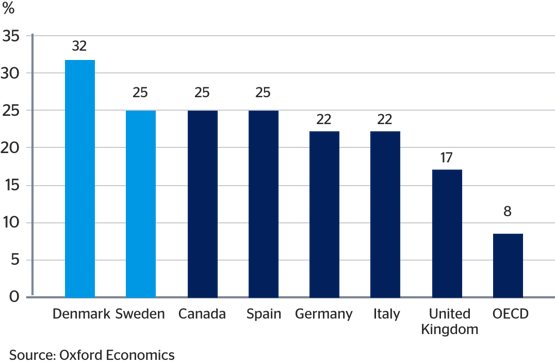

Both Denmark and Sweden’s economies are particularly integrated into global value chains; both economies have a high dependence on trade. OECD Trade in Value Added data provides a clear illustration showing that both countries’ exports possess a relatively high proportion of foreign content (Fig 2).1

For Denmark the foreign value-added content of exports is 32% whilst for Sweden it is 25%. This is more than triple the proportion for the OECD as a whole. These relatively high figures imply that successful delivery of imported goods is important for success in Denmark’s and Sweden’s exporting companies. Foreign firms – and multinational enterprises especially – are likely to be behind Denmark’s and Sweden’s high levels of integration into global value chains. Almost 40% of Danish goods exports are by Danish parent multinational corporations, at the upper end of European countries.2 (Comparable data for Sweden is not available).

1. OECD. 2023. Trade in Value Added (TiVA) Principal Indicators. Accessed September 2023.

2. OECD. 2017. Denmark trade and investment statistical note. Accessed September 2023.

Fig 2: Foreign value added as a share of total in different countries exports, 2022

Both Denmark and Sweden’s economies are particularly integrated into global value chains; both economies have a high dependence on trade. OECD Trade in Value Added data provides a clear illustration showing that both countries’ exports possess a relatively high proportion of foreign content (Fig 2).1

For Denmark the foreign value-added content of exports is 32% whilst for Sweden it is 25%. This is more than triple the proportion for the OECD as a whole. These relatively high figures imply that successful delivery of imported goods is important for success in Denmark’s and Sweden’s exporting companies. Foreign firms – and multinational enterprises especially – are likely to be behind Denmark’s and Sweden’s high levels of integration into global value chains. Almost 40% of Danish goods exports are by Danish parent multinational corporations, at the upper end of European countries.2 (Comparable data for Sweden is not available).

1. OECD. 2023. Trade in Value Added (TiVA) Principal Indicators. Accessed September 2023.

2. OECD. 2017. Denmark trade and investment statistical note. Accessed September 2023.

Fig 2: Foreign value added as a share of total in different countries exports, 2022

Geopolitical challenges facing firms involved in the trade in goods

Geopolitical tensions tend to increase barriers to trade. For example, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to many Western countries imposing sanctions on Russia.3 To investigate the threat from the further fragmentation of trade from increased geopolitical tensions and the resulting tariffs, sanctions or bans to trade, we look at what proportion of goods are sold to geopolitical allies versus other nations. To do this, we use the voting patterns in the United Nation’s General Assembly resolution to deplore the Russian invasion of Ukraine.4 For both Denmark and Sweden, approximately 6% of goods exports came from countries that voted against or abstained on the Resolution. Regarding goods imports, the proportion coming from countries that voted against or abstained on the Resolution was 12% for Denmark and 10% for Sweden. China and India, who abstained, are the largest trading partners for the two Nordic countries in both exports and imports.

3. IMF. Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism. Accessed September 2023.

4. United Nations. 2022. Aggression against Ukraine: resolution/adopted by the General Assembly. Accessed 10 August 2023.

5. The World Bank. 2023. FY24 List of Fragile and Conflict-affected Situations. 10 July 2023.

Another source of risk relates to countries that are institutionally and socially fragile or are affected by violent conflict as judged by the World Bank’s definition for this year.5 Fortunately for stability, Denmark and Sweden export and import less than 1% of their goods to and from these countries.

Geopolitical tensions tend to increase barriers to trade. For example, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to many Western countries imposing sanctions on Russia.3 To investigate the threat from the further fragmentation of trade from increased geopolitical tensions and the resulting tariffs, sanctions or bans to trade, we look at what proportion of goods are sold to geopolitical allies versus other nations. To do this, we use the voting patterns in the United Nation’s General Assembly resolution to deplore the Russian invasion of Ukraine.4 For both Denmark and Sweden, approximately 6% of goods exports came from countries that voted against or abstained on the Resolution. Regarding goods imports, the proportion coming from countries that voted against or abstained on the Resolution was 12% for Denmark and 10% for Sweden. China and India, who abstained, are the largest trading partners for the two Nordic countries in both exports and imports.

3. IMF. Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism. Accessed September 2023.

4. United Nations. 2022. Aggression against Ukraine: resolution/adopted by the General Assembly. Accessed 10 August 2023.

5. The World Bank. 2023. FY24 List of Fragile and Conflict-affected Situations. 10 July 2023.

Another source of risk relates to countries that are institutionally and socially fragile or are affected by violent conflict as judged by the World Bank’s definition for this year.5 Fortunately for stability, Denmark and Sweden export and import less than 1% of their goods to and from these countries.

Key things to watch

- Winter energy: Denmark and Sweden are less dependent than many other EU nations on the external energy market – but not immune to shocks to it – and the 2023/24 winter will test both Denmark and Sweden’s energy systems. Denmark used 37% less gas in 2022 compared with 2021 and the government will likely work to persuade consumers to use less gas again this year. The construction of a new pipeline connecting Denmark and Poland, resumption of plans to tap Danish gas fields, and the implementation of renewable energy targets place Denmark in a strong position for the coming winter. Sweden’s mix of nuclear, biomass, and low usage of natural gas and oil also place it in a strong position. However, both will be affected by wider EU energy challenges and will likely seek to export energy where possible, challenging their domestic markets.

- Geopolitical concerns: Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 took many by surprise, businesses are more aware of the potential impact of political crises on global trade, be it via the imposition of sanctions or the need to close entities for reputational reasons. Sweden’s subsequent decision to apply for NATO membership represents a significant shift in its foreign policy and means that it can no longer present itself as a neutral player, with likely impacts on its trading relationships.

- Energy investment: Both Denmark and Sweden have big plans to invest in renewable energy – on and offshore. Denmark wants to harness offshore wind by building so-called energy islands – a project which is expected to become clearer alongside plans for joint investment with Germany. The government will also move towards further decisions on its recently flagged carbon capture, usage, and storage plans. Sweden intends to recommence uranium mining in addition to permitting the construction of new nuclear plants and further details of these plans are expected later in 2023. The government is also pushing for greater investment in offshore wind but plans look likely to face opposition from environmental NGOs and shipping companies.

- Winter energy: Denmark and Sweden are less dependent than many other EU nations on the external energy market – but not immune to shocks to it – and the 2023/24 winter will test both Denmark and Sweden’s energy systems. Denmark used 37% less gas in 2022 compared with 2021 and the government will likely work to persuade consumers to use less gas again this year. The construction of a new pipeline connecting Denmark and Poland, resumption of plans to tap Danish gas fields, and the implementation of renewable energy targets place Denmark in a strong position for the coming winter. Sweden’s mix of nuclear, biomass, and low usage of natural gas and oil also place it in a strong position. However, both will be affected by wider EU energy challenges and will likely seek to export energy where possible, challenging their domestic markets.

- Geopolitical concerns: Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 took many by surprise, businesses are more aware of the potential impact of political crises on global trade, be it via the imposition of sanctions or the need to close entities for reputational reasons. Sweden’s subsequent decision to apply for NATO membership represents a significant shift in its foreign policy and means that it can no longer present itself as a neutral player, with likely impacts on its trading relationships.

- Energy investment: Both Denmark and Sweden have big plans to invest in renewable energy – on and offshore. Denmark wants to harness offshore wind by building so-called energy islands – a project which is expected to become clearer alongside plans for joint investment with Germany. The government will also move towards further decisions on its recently flagged carbon capture, usage, and storage plans. Sweden intends to recommence uranium mining in addition to permitting the construction of new nuclear plants and further details of these plans are expected later in 2023. The government is also pushing for greater investment in offshore wind but plans look likely to face opposition from environmental NGOs and shipping companies.

Macroeconomic risks to the export and import of goods

Trade in goods is sensitive to changes in the economic cycle. Our central forecast is that Danish and Swedish imports of goods will contract by 1.9% and 6.5% in 2023 respectively. For both countries, goods imports are expected to revert to growth in 2024 and 2025 with growth of between 2-3%. Export growth is expected to be positive in the next three years with the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for goods being 2.7% for Denmark and 1.9% for Sweden.

However, as forecasters cannot predict unforeseen events, it is beneficial to examine how Denmark’s and Sweden’s exports and imports of goods could be affected under negative macroeconomic scenarios.6 Our forecasts suggest that the materialization of an asset price crash would be the worst downside scenario for the outlook of Nordic imports and exports in the near/medium term. Under an asset price crash, Danish exports in 2025 are expected to be 4.6% lower than the central forecast (Fig. 3). Sweden’s exports are expected to be 4.3% lower. Denmark’s imports are expected to be 5.1% lower whilst Sweden’s are expected to be 3% lower.

6. Oxford Economics. 2023. Oxford Economics Global Scenarios Service. Accessed 5 September 2023.

Fig 3: Impact of asset price crash and tighter credit conditions on Nordic exports and imports of goods (in real terms), % difference from baseline scenario, 2025

Trade in goods is sensitive to changes in the economic cycle. Our central forecast is that Danish and Swedish imports of goods will contract by 1.9% and 6.5% in 2023 respectively. For both countries, goods imports are expected to revert to growth in 2024 and 2025 with growth of between 2-3%. Export growth is expected to be positive in the next three years with the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for goods being 2.7% for Denmark and 1.9% for Sweden.

However, as forecasters cannot predict unforeseen events, it is beneficial to examine how Denmark’s and Sweden’s exports and imports of goods could be affected under negative macroeconomic scenarios.6 Our forecasts suggest that the materialization of an asset price crash would be the worst downside scenario for the outlook of Nordic imports and exports in the near/medium term. Under an asset price crash, Danish exports in 2025 are expected to be 4.6% lower than the central forecast (Fig. 3). Sweden’s exports are expected to be 4.3% lower. Denmark’s imports are expected to be 5.1% lower whilst Sweden’s are expected to be 3% lower.

6. Oxford Economics. 2023. Oxford Economics Global Scenarios Service. Accessed 5 September 2023.

Fig 3: Impact of asset price crash and tighter credit conditions on Nordic exports and imports of goods (in real terms), % difference from baseline scenario, 2025

Advice for business

Businesses should look to undertake due diligence of overseas trading partners, including checks on their experience and trustworthiness within the industry, their relationships with government officials, and their reputation for management and production. Consulting with other businesses who are familiar with the suppliers or country may be beneficial. Constructing clear contracts will also protect against any issues that may arise with overseas trading partners. Terms and conditions in contracts should be carefully listed and include details about rights and responsibilities regarding dispute resolution.

Alongside supplier-specific risks, country-specific risks should also be considered – these include economic, political, and structural risks. Exporters could experience political risk if the buyer’s country imposes new import restrictions. These could range from import bans to tariffs and new product regulations. For countries that are suffering from economic problems such as high inflation, risks could include customers experiencing difficulties paying.

When exporting to countries vulnerable to economic risks, consider payment in advance or through a letter or credit (where the bank promises to pay if the buyer cannot).

Using the services of a country’s trade promotion agency can also help businesses navigate the complexities associated with dealing with international trading partners. This includes advice (often free) on customs and export conditions in various export markets. If businesses are considering exporting to new countries, it may be advantageous to look at undertaking a strategic alliance or joint venture. Alongside the division of financial risk, an alliance reduces obstacles in getting products to new markets.

Businesses should look to undertake due diligence of overseas trading partners, including checks on their experience and trustworthiness within the industry, their relationships with government officials, and their reputation for management and production. Consulting with other businesses who are familiar with the suppliers or country may be beneficial. Constructing clear contracts will also protect against any issues that may arise with overseas trading partners. Terms and conditions in contracts should be carefully listed and include details about rights and responsibilities regarding dispute resolution.

Alongside supplier-specific risks, country-specific risks should also be considered – these include economic, political, and structural risks. Exporters could experience political risk if the buyer’s country imposes new import restrictions. These could range from import bans to tariffs and new product regulations. For countries that are suffering from economic problems such as high inflation, risks could include customers experiencing difficulties paying.

When exporting to countries vulnerable to economic risks, consider payment in advance or through a letter or credit (where the bank promises to pay if the buyer cannot).

Using the services of a country’s trade promotion agency can also help businesses navigate the complexities associated with dealing with international trading partners. This includes advice (often free) on customs and export conditions in various export markets. If businesses are considering exporting to new countries, it may be advantageous to look at undertaking a strategic alliance or joint venture. Alongside the division of financial risk, an alliance reduces obstacles in getting products to new markets.

Taking out insurance coverage can mitigate against financial losses associated with issues such as damage, theft and cargo losses. Multinational programmes offer packages which means businesses do not have to navigate complexities associated with having separate insurance policies for each of the countries they operate in.

Although there are risks associated with international trade it’s important to bear in mind that both Denmark and Sweden’s businesses benefit hugely from the ability to trade across borders. By allowing businesses to reach more customers, trade creates economies of scale which pushes costs down. Danish and Swedish firms also benefit from being able to source cheaper inputs from abroad, which helps to make their products more price competitive.

Taking out insurance coverage can mitigate against financial losses associated with issues such as damage, theft and cargo losses. Multinational programmes offer packages which means businesses do not have to navigate complexities associated with having separate insurance policies for each of the countries they operate in.

Although there are risks associated with international trade it’s important to bear in mind that both Denmark and Sweden’s businesses benefit hugely from the ability to trade across borders. By allowing businesses to reach more customers, trade creates economies of scale which pushes costs down. Danish and Swedish firms also benefit from being able to source cheaper inputs from abroad, which helps to make their products more price competitive.

This report has been developed for QBE by Control Risks and Oxford Economics

This report has been developed for QBE by Control Risks and Oxford Economics

2023 forecast for the Danish and Swedish life sciences sector

What is the outlook for the Danish and Swedish life sciences sector and how could limited diversification impact growth prospects

Sign-up to be notified about future articles from the Sector Resilience Series, and other thoughts, reports or insights from QBE.